By Xing Yi in London | China Daily

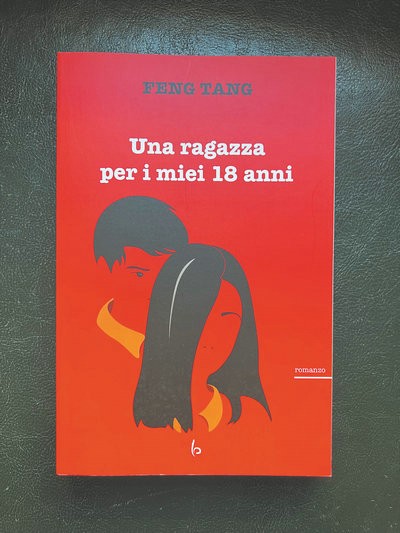

of Give Me a Girl at Age Eighteen. [Photo by Xing Yi/China Daily]

Confucius has said that one should know the mandate of heaven upon turning 50. But Feng Tang seems to have known what heaven mandated him to do long ago. When he had just emerged as a young writer two decades ago, he said: “I owe 10 novels to heaven.”

In China’s literary circle, Feng is considered a crossover wunderkind.

He is a Beijinger who studied gynecology in the country’s top medical school and qualified as a doctor in the 1990s, before getting an MBA diploma in the United States. He then entered a top consultancy firm and, later, got onto the executive management boards of two big companies in China.

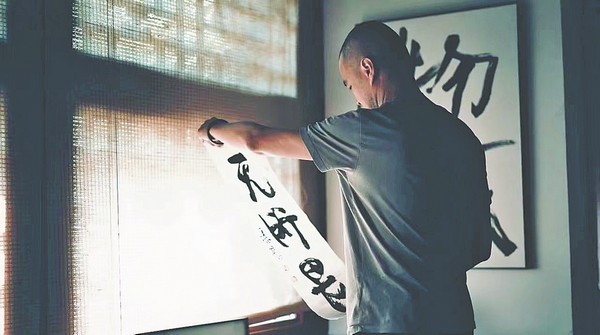

If Feng’s crossover from a doctor to businessman was not surprising enough, consider this: He has since published six novels, several anthologies of his essays, poems and a series of books on managerial tips. At the same time, he has become a well-known artist whose calligraphy has been featured in exhibitions, sold at auctions and adapted into a font.

Last year, at the age of 50, Feng left Citic Capital, where he had been a venture capitalist in the field of healthcare for six years. He said he wanted to take a rest at what he described as halftime in his life. But Feng was stuck in the United Kingdom due to pandemic restrictions. He managed to turn it into a long sojourn.

In a cafe next to Westminster Chapel in London, we met Feng, an author-at-large in a white hoody with a line of Chinese characters that reads: “I don’t want to leave the world to those whom I hold in contempt.”

“As I finally get the chance to enjoy some quiet time, I ask myself if I had a car accident, what I would regret most?” Feng says.

“I would certainly miss good books I haven’t got time to read, the calligraphy and paintings I haven’t drawn, and the novels I haven’t penned.”

Feng has indulged in the freedom of not having to be on business trips every two or three days like before, when he was a member of the business elite. Instead, he reads books and records lessons for his podcast, practices calligraphy every day and jots down a few hundred words for his books.

Feng says that The Golden Line, the latest installment in his management book series, is set to be published in December, and another novel, with a tentative title of My Father Knows All the Fishes, is in the process of being reviewed by the publisher.

“The novel about my father is the first installment of a semi-memoir trilogy, which will be followed by one about my mother, and another one about my elder brother and sister,” he says. “I want to name this trilogy after the neighborhood where I was born and raised-Chuiyangliu (‘weeping willow’) in Beijing.”

As a novelist, Feng became controversial for his blunt description of sexuality.

His popular semi-autobiographical Beijing trilogy was published between 2001 and 2007, which dealt with the coming-of-age story of a young man on his journey from high school to medical college, and then into the world of work.

Carlos Ottery, a former editor at The World of Chinese, an English magazine and web portal of the Commercial Press, describes Feng’s early works as “a teenage diary” in his review of Give Me a Girl at Age Eighteen, Feng’s novel which was translated into English in 2019.

“While it is possible for a novelist to have success through an obsessional relationship with sex,” writes Ottery, adding that Feng references both Henry Miller and D.H. Lawrence as inspirations.

He adds that “Eighteen does capture something of what it was like to come of age in Beijing as part of a post-70s generation … caught within an ideological reset of free-market reforms and Westernization”.

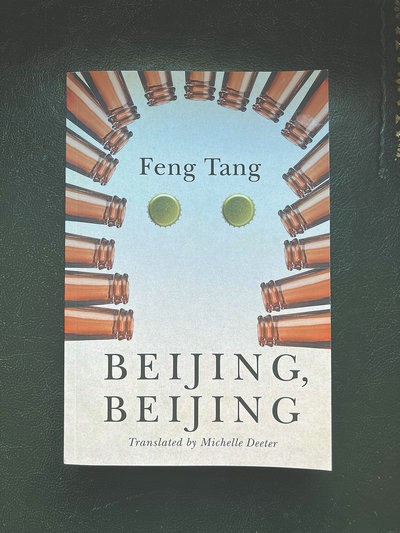

Michelle Deeter, translator of Feng’s Beijing, Beijing, says she found the novel very interesting when she was given a sample to read by Amazon Crossing, which made her decide to take on the translation. The book’s English version was published in 2015.

“It uses offensive language. It can discuss topics that a US reader might find sensitive or uncomfortable,” says Deeter about the biggest difficulty of retaining the style of Feng’s writing while making it a page-turner.

“I would say Henry Miller maybe is more offensive, rude and racy and pushing the boundaries. However, Feng Tang clearly admires him, so there are certain styles or certain choices that do remind me of Miller,” she says.

Some of Feng’s books were also translated into Italian and French. However, Feng himself was disinterested in seeing his novels being translated into foreign languages.

“Literature is very difficult to render in another language, and I think most foreigners won’t be interested in my stories,” he says.

“Maybe they would be more interested in reading the stories about China when it was still poor and lagging behind, but my works are about young people experiencing the period of China’s rapid transition.”

Feng says his generation, which was born in the 1970s when China started to adopt reform and opening-up, has witnessed the rapid change of China, and the growth of its economic power has made Chinese people more confident in dealing with the world. The change and the ensuing globalization have enabled Feng to “view the world as a level playing field”.

Feng says he noticed that many management theories from the West cannot be applied well in the Chinese market. So, in 2018, he started writing books on business and management which later became a series called Getting Things Done.

“They present a management theory blended with Chinese traditional wisdom,” he says, adding that his sources are from methodologies from McKinsey & Co where he had worked, the Chinese history classics, such as Zizhi Tongjian (Comprehensive Mirror in Aid of Governance), and his firsthand experience of working in two State-owned companies.

Feng enjoys his stay in London, where he runs along the River Thames three times a week, and finds his neighborhood very convenient for grocery shopping, strolling in the park and borrowing books.

“It has reminded me of living in a Beijing hutong (a traditional residential alleyway) where everything is close by,” he says.

“I like the rainy season of the British winter, because one finds inner peace in rainy days-then the details in your memory emerge,” Feng says about writing about his late father. “The smell of my father’s dishes, his calling us to dinner …they all come back to me.

“A novelist relies not on theory, not even on story, but on those kinds of details,” he says.

“I worried about experiencing writer’s block when I first got stuck in London, but now it seems I still have the ability to write and express myself.”